By Dr. Sarah Bennett, NMD / April 21, 2021

On a daily basis our bodies continually encounter poisons, chemicals, drugs, and toxins.

So thank goodness that detoxification is a natural process carried out by the emunctory organs of the body, primarily the liver and kidneys.

Some of you may be thinking. “I purchase organic produce, I think I’m safe.”

Well, I’m sorry to burst your bubble but that’s not going to do the trick. In fact, you might be shocked when you find out where some of these harmful toxins are found! Yes, pesticides on produce but toxins are found in many unexpected places such as baby bottles, and ice cream!

Throughout this article, I hope to inform you about the most common toxins of daily exposure, where they are found, symptoms and illnesses they cause, even how to identify them on labels to help avoid exposure in the future.

The first step is to pinpoint your potential exposures, and the second step is to avoid them.

After all the three most important principles of environmental medicine are “avoid, avoid, avoid” (1).

Bisphenol A commonly known as BPA is a chemical compound primarily used in the production of plastics such as water bottles, baby bottles, and food containers, but is also used to create adhesives, paint, coatings, sealers, and even used in food preparation processes.

BPA has been used since the 1950s but recently the production of this chemical has skyrocketed to 6 billion pounds per year worldwide, making BPA one of the highest volume chemicals produced in the world. (1) The United States alone produces upwards of 2 billion pounds of BPA per year. (2)

The CDC found that over 90% of U.S. citizens aged 6 and older have detectable levels of BPA in the urine, meaning we are exposed to BPA at a very high level. (7)

The primary route of exposure to BPA is through eating or drinking food that has come in contact with a container or product containing the compound.

Although BPA has been used in high quantities since the 1950s, studies to determine toxicity and carcinogenicity have only been performed since the 1970s.

Slowly studies began to document BPAs harmful effects, including a study conducted in 2012 finding low doses of BPA are associated with an increased risk of breast and prostate cancer. (3)

Since, BPA has been found to have numerous negative effects on health, with studies showing that it most significantly affects infants and fetuses. (3)

The numerous detrimental health effects of BPA include but are not limited to:(4,5,54)

In 2012, due to consumer concern, the Food and Drug Administration banned the use of BPA in products designed for infants, but still considers the current use of BPA in other products such as water bottles, food containers, and even food preparation processes to be safe. (4)

The European Chemical Agency (ECHA) announced in 2017 that BPA should be considered a substance of very high concern due to the serious effects of its endocrine-disrupting properties. (8)

BPA has been fully banned in both Canada and Europe, but despite scientific recommendations the United States maintains legal use of this product.

To make matters worse, in 2015 a bill attempting to force the FDA to ban BPA was rejected after the American Chemical Council donated a large amount of money. (9)

Recently, manufactures have begun to substitute the use of BPA for other chemicals such as bisphenol S (BPS), bisphenol F (BPF), and diphenyl sulfone. Despite these efforts, these chemicals also display adverse health effects similar to those of BPA, such as obesity, neurological disorders, metabolic disease, and endocrine disruption. (6)

So yes, BPA has been banned from our babies’ products. But despite the BPA free labels, don’t be fooled, these alternative chemicals currently being used without toxicity testing such as BPS are not required to appear on any product labels.

Phthalates are a group of chemicals called plasticizers used to increase the flexibility of plastics and as a solvent in detergents and personal care products.

These chemicals are commonly found in synthetic (plastic) clothing, vinyl flooring, adhesives, detergents, personal care products such as soap, hair spray, nail polish, shampoos, plastic gloves, food storage containers, plastic wrap, inflatable toys, children’s toys, even medical products such as plastic tubing and blood storage bags. (11,14)

Despite the fact that phthalates have been used in manufacturing since the 1920s, the first United States study to determine the exposure rate of the population to these chemicals did not take place until 2013. (14)

Shockingly this study found that the primary sources for exposure to phthalates are grains, beed, pork, chicken, and milk products. (14)

In addition, studies have since found that phthalate exposure can lead to many adverse health effects, including but not limited to:

Due to the harmful effects of exposure, as of 2005 Europe has banned the use of phthalates in manufacturing, and since nine other countries including Mexico, Japan, and Argentina have also banned the use of these chemicals.

Although late to the game, as of April 2018 the United States banned the use of phthalates in children’s toys and child care products. (15)

Despite the known adverse health effects caused by phthalate exposure, the United States has yet to fully ban these chemicals from manufacturing.

Phthalates are still commonly found in large amounts of products sold in the U.S. today, and to make matters worse there are no requirements for labeling of these chemicals.

Although labeling is not required, some products such as personal care items may include phthalates on the ingredient labels.

The first step is to avoid toxic exposure and therefore alway recommend checking the ingredients list of any item prior to purchase.

The most common phthalates seen on ingredient list are listed below:

Heavy metals are a class of highly dense metals that occur naturally in nature.

These metals break down easily into the air, soil, and water making exposure frequent and difficult to avoid.

In the body, these metals have an affinity to bind sulfur compounds inhibiting the proper functioning of enzymes and metabolic processes in the body, ultimately causing detrimental health effects.

Risk of exposure to these heavy metals has skyrocketed since industrialization. Although regulations have tightened these heavy metals are to this day used in production of food and goods.

Arsenic occurs naturally in two forms: organic and inorganic, each of which containing a different molecular structure. This difference in structure makes inorganic much more toxic after exposure.

Arsenic is minimally absorbed through the skin and therefore exposure primarily results from ingestion and inhalation.

Arsenic toxicity is a global problem affecting millions of people world wide. Exposures occur due to natural contamination of drinking water and soil as well as through contact with arsenic containing manufactured goods and products.

Industrially used arsenic can be found in wood preservatives, glass, pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, fertilizers, and until recently animal feed.

In 2015 the United States fully banned the use of arsenic based drugs in animal feeds due to finding high levels of arsenic in meats sold for consumption by the american population.

Prior to this date, these medications were added to animal feed as an antibiotic to stimulate faster weight gain, decrease chances of infection, and provide a healthy color to the meat.

Although arsenic has been banned from use in livestock feed, it is still used in large quantities as pesticides.

Due to the ongoing historic use of arsenic-based pesticides in farming, soil arsenic concentrations have become increasingly high, finding >100mg/kg of arsenic in the soil of many orchards around the United States. (16) In addition, this arsenic is absorbed by

This arsenic is now being found in the majority of food products. Studies have found that the higher the soil concentrations of arsenic, the higher the crop concentrations. (16)

The arsenic from the soil and water is directly contaminating our food supply and our population.

The foods with the highest arsenic concentrations tend to be meat, fish, and poultry. (18) Over time, the consumption of crops and feed containing arsenic lead to an even higher concentration of arsenic within the meat produced.

Symptoms of arsenic toxicity:

The environmental protection agency (EPA) requires that U.S. drinking water contain an arsenic concentration of 10ppb or below due to the risk of adverse health effects. (20) Long term exposure to arsenic at levels above 10 ppb have been linked to an increased risk of developing chronic health problems, (19)

Despite causing a multitude of adverse health effects there are no regulations in place regulating concentrations of arsenic in food products nor require labeling of products containing arsenic compounds in the United States. (20)

Although the United States has regulated the use of lead in consumer-based products since 1986, exposure and resulting toxicity still occur at an alarming rate. (21)

Approximately 500,000 children in the United States under the age of 6 years old have toxic blood lead levels, and additionally, 3.6 million homes with young children are estimated to provide hazardous exposure to lead paint. (22)

Young children and infants are at the highest risk of lead exposure and toxicity due to their smaller size, higher absorption rates, closer proximity to the ground, and curiosity for surroundings. (22)

In children between the ages of 1 and 5 years old, blood lead levels higher than 5 mcg/dL are considered toxic and linked to long-term health effects. (23)

In both adults and children lead is primarily absorbed via inhalation and ingestion, although lead may be absorbed through the skin as well. (24)

Sources of lead exposure are still primarily from contact with lead containing products manufactured to 1978.

The list of symptoms associated with lead toxicity is extensive and broad. A few of the common symptoms associated with lead toxicity include:(25)

Cadmium toxicity is primarily caused by cigarette smoking or an occupational related exposure.

Common Cadmium exposure sources include:

Although cadmium can be found in many foods, due to small concentration and low absorption rates through the GI tract these foods are not toxic.

On the other hand, if high quantities are ingested or inhaled numerous adverse health effects are likely to result.

The most common symptoms of cadmium toxicity include: (26)

“Mercury is considered by WHO as one of the top ten chemicals or groups of chemicals of major public health concern.” (27)

In addition to natural erosion, mercury is used in various industrial and mining operations, including but not limited to gold mining and coal-burning power plants, which has to lead to contamination to (28)

As a result mercury ‘hot spots’ have been created, meaning the land, and water contains high levels of toxic mercury compounds. These compounds consequently accumulate to high levels in the plants and animals in the area. (28)

Consequently, eating certain types of fish is considered the primary risk for exposure to mercury. (29) This being said there are other avenues of exposure, some of the most common are listed below:

There are 3 primary chemical forms of mercury, methylmercury (organic mercury), inorganic mercury, and elemental mercury.

Of these three forms methylmercury is considered to be the most toxic, and unfortunately this is the form found in high quantities of contaminated fish.

But don’t be fooled, each of these forms of mercury can cause organ damage and many symptoms of toxicity.

Mercury toxicity is known to cause damage to the neurological system and brain, lungs, kidneys, heart, and immune system.

Fetuses, infants, and small children are the most sensitive to the negative health effects caused by mercury toxicity, often leading to long-term damage of the developing nervous system which can result in learning disabilities. (28,29,31)

Some of the most common symptoms of toxicity for each form are listed below:

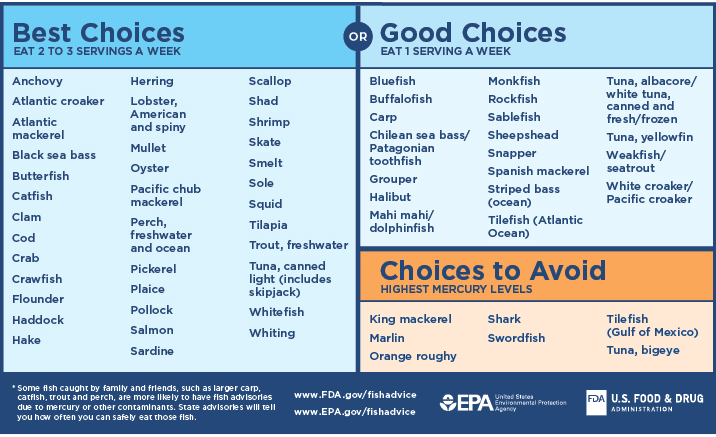

The first step for all environmental toxins is to avoid exposure. Be sure to check product labels and avoid eating fish known to have mercury contamination. The chart below was created by the FDA to help guide fish choices based on mercury levels. In addition to adjusting fish intake based on this chart, be sure to check local fish advisories when eating locally caught fish.

(6)

Pesticides are man-made chemicals designed to kill or control pests. There are many types of pesticides, including but not limited to: herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, insect repellent, animal repellent, rodenticide. Each of which is designed to control or kill a particular type of pest.

Although there are clear benefits to warding off unwanted pests, these chemicals come with known toxicities.

Many people discount the negative health effects of pesticides on health… But the health effects are not small or insignificant.

The World Health Organization and UN Environment Programme estimate that severe pesticide poisoning affects 3 million agricultural workers annually, leading to 18,000 deaths. (33)

Out of all pesticides, fungicides have been shown to be the most toxic followed by herbicides and insecticides, with Round Up ranking as one of the most toxic. These are the substances sprayed in large quantities over the majority of produce farmed in the United States and worldwide. (34)

Some of the most common classes of pesticides with documented negative health effects are listed below:

The negative side effects are numerous and even affect those who are not experiencing acute occupational contact.

This should not be surprising, since these chemicals are used to ward off, paralyze, even kill pests.

Many of the negative health effects linked to the toxic effects of pesticides are listed below.

You may be thinking “Well, Its a good thing I eat Organic.”

Don’t let the term ‘Organic’ fool you! Certified organic produce is still grown with pesticides, Organic pesticides.

Shockingly, certain organic pesticides have been shown to have higher toxicity than similar synthetic pesticides. And to top it off, organic pesticides are commonly used in higher quantities due to lower efficacy rates, leading to products containing a higher pesticide residue. (36)

So how do we avoid exposure to these toxic chemicals?

There are many local farmers that offer truly chemical-free produce. One of my favorite local chemical-free produce delivery services is your farm foods

Common household products such as cleaners, cosmetics, body products frequently contain toxic chemicals known to cause mild to severe health side effects.

Although, severe acute exposures are rare and mostly affect small children. The average American is regularly exposed to small amounts of these toxic chemicals daily, which over time can have harmful effects.

Listed below are some of the toxic chemicals frequently found in many household cleaners, cosmetics, and personal products with respective health effects.

Chlorine is currently used in household cleaners such as bleach and multipurpose sprays for its anti-microbial, and whitening qualities. In addition, chlorine is used in the water purification process for its antimicrobial properties, explaining the presence of chlorine in tap water.

Acute chlorine exposures occur primarily due to occupational or accidental gas inhalation which can cause significant irritation and even long-term damage to the eyes and lungs. Keep in mind that using chlorine-containing cleaning products can result in similar side effects due to chlorine gas exposure. (37,38)

Chronic exposures are more likely to occur due to oral consumption of tap water. Long-term ingestion of chlorinated water has been associated with an increased risk of antibiotic resistance and colon cancer.(39,40)

Ammonia is commonly used in household cleaning agents, glass cleaners, fertilizers, and antimicrobial agents in food preparation. Exposures may occur due to inhalation, skin contact, and ingestion, shown to be corrosive and cause damage to contacted cells in the body. (41)

Acute exposures may result in corrosive injury to the skin, and mucous membranes of the eyes, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract.

Chronic exposure to Ammonia may cause asthma, chronic cough, chronic irritation to the skin and eyes, even pulmonary fibrosis.

Glycol Ethers are commonly used in cleaning products, liquid soap, and cosmetics which for the general public is the primary source of exposure. (42)

Acute exposures may cause mild to severe symptoms depending on level of contact. These symptoms may include:

Chronic exposure to Glycol ethers is known to cause significant long term side effects including:

Although, more research is needed is chronic exposure to Glycol ether may be linked to an increased risk of cancer and decreased fertility. (42)

Triclosan is an antibacterial chemical frequently used in body products such as shampoos, soaps, conditioners, toothpaste, and mouth washes, cleaning supplies, and pesticides.

Triclosan has been shown to cause allergies, asthma, mitochondrial dysfunction, disrupt neurological signaling, alter immune function, thyroid dysfunction, decrease birth weights, increase the likelihood of spontaneous abortions, and cancer. (43)

Although, the FDA recently banned the use of Triclosan in certain soap products, it is so widely used that 75% of the American population is likely to be exposed to Triclosan through use of consumer products.(43)

2-Butoxyethanol is a chemical found in silk screening agents, and household cleaners.

Alcohol, the ancient tonic known for its ability to cause social lubrication, relaxation, and intoxication, can and often is dangerous in high quantities.

Alcohol has many short-term and long-term adverse effects ranging from increased risk of injury to risk of addiction, brain damage, diabetes, liver damage, birth defects, and more.

It is widely known that consuming high quantities of alcohol in a short window of time can lead to alcohol poisoning, an emergency situation when alcohol begins to cause serious even fatal toxicity symptoms.

(44)

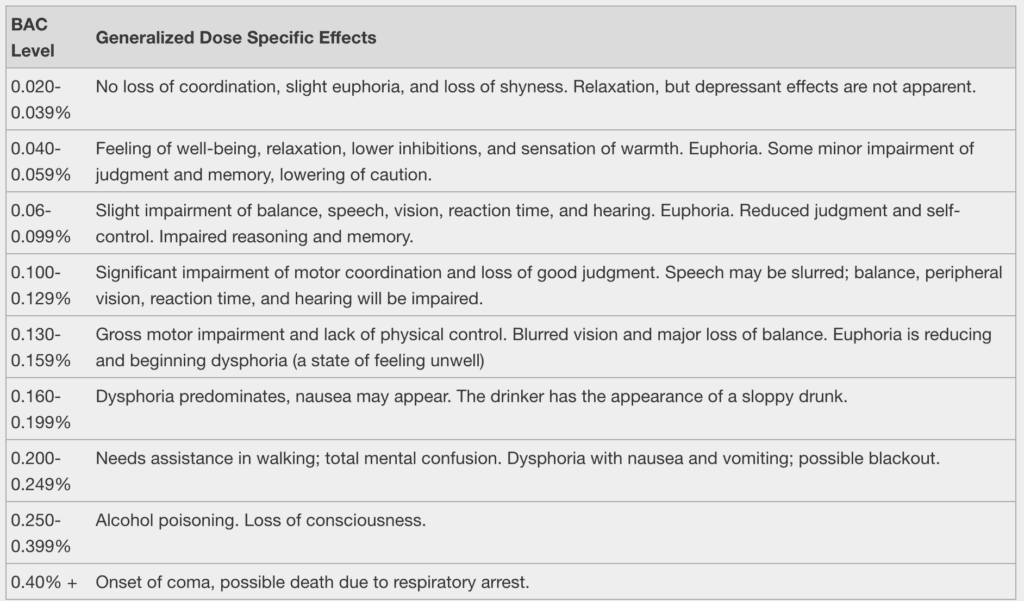

As shown in the chart above, intoxication effects begin to present at a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.020% whereas alcohol poisoning occurs at a BAC of 0.250% or greater.

Common signs of alcohol intoxication include:

Signs of acute emergency alcohol poisoning additionally include:

If you are thinking “ Well, I’m in the clear because I rarely if ever drink to the point of intoxication, much less alcohol poisoning.” Alcohol poisoning is not the only risk of alcohol consumption.

Long term heavy alcohol consumption is an enormous risk factor for many diseases, such as:

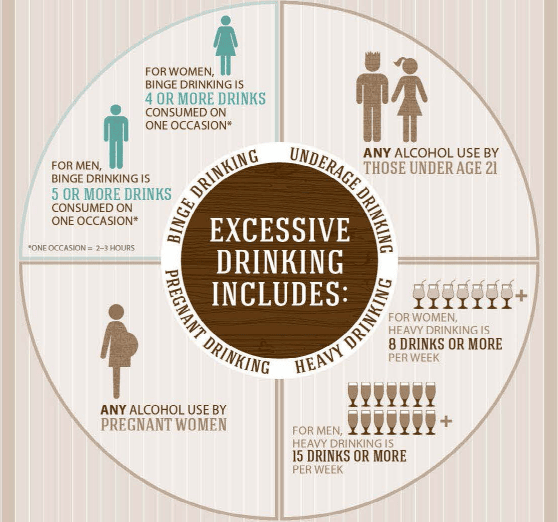

Heavy alcohol consumption is defined as:

Women- Consuming 4+ drinks on one occasion, or 8+ drinks over the course of a week.

Men- Consuming 5+ drinks on one occasion, or 15+ drinks over the course of a week. (50)

Alcoholism is a serious overlooked public health crisis, calculated to affect 1 in 8 American adults and causes 95,000 deaths each year, in the United States alone. (3)

(7)

To help determine your daily, weekly, or monthly alcohol consumption. I have listed below a guide to what is considered 1 drink.

The mechanism by which alcohol causes damage to the liver is still poorly understood and controversial. What is well known is that alcohol consumption depletes certain nutrients essential for the phases of detoxification and antioxidant functionality.

Some of these nutrients include:

As discussed above these nutrients are essential for the proper functionality of both phase 1 and 2 detoxification through the liver. Chronic alcohol use has the potential to make these detoxification pathways sluggish causing toxins to build up in the body increasing toxicity symptoms and damage caused by free radicals.

All of the recommended detoxification protocols recommended at Natural Med Doc include the nutrients listed above, which replenishes nutrient deficiencies and improves functionality of the liver’s detox pathways.

34.2 million American adults report smoking cigarettes, and 8.1 million American adults report vaping. That’s a total of 42.3 million adult Americans that knowingly ingest toxic chemicals on a regular basis that provide no real benefit or euphoric effects! (54,255)

If anything it is widely known to cause adverse health effects and even shorten a person’s life span.

Quite frankly, cigarette smoking and vaping are possibly the most pointless harmful habits that are widely accepted in cultures globally.

Not only do cigarettes and vape juices contain nicotine which is highly addictive, they also contain an absurd amount of known carcinogens and toxins.

To be more specific, cigarette smoke contains approximately 7,000 or more chemicals, of which at least 69 are known carcinogens. (56)

A few of the most harmful chemicals in cigarettes are listed below. But don’t forget, that’s just 22 of 7,000!

Well, vaping is better right? Not exactly. Vaping is a newer trend that has much less research to determine this at the present moment. What is known about vaping is hat the juice contains up to 113 different chemicals, many of which are also included on the above list ( therefore known to be toxic). Also, there are many negative health effects that are starting to be linked to vaping, but we will get to this later.

A few of the toxins found in Vape juices are listed below.

Remind me again why some many people are chronic smokers and vapers?

This is because most people report that they started smoking or vaping when they were a teenager or young adults due to social influences. In other words, for the “cool factor”. (57)

Despite your political affiliations, government officials have to be commended for taking action to support the health of our younger generations by passing legislation in December of 2020 to raise the legal age for tobacco sales from 18 to 21. (58)

So what are the long term effects of the habits? Listed below are some of the major health effects associated with smoking cigarettes and vaping.

Negative health effects caused by cigarette smoking:

Due to the newness of the vaping trend, the risk profile of this habit is still being developed. Although more time and research is needed to fully understand the impact of vaping on health. It is known that vaping is associated with the following negative health effects.

So there should be no surprise that cigarette smoking is shown to cause several nutrient deficiencies. As listed above, these nutrients are essential for proper functioning of the detoxification pathways in addition to offering substantial antioxidant effects. Cigarette smoking is shown to cause deficiencies or altered utilization of the nutrients listed below. (More time and research is needed to determine if vaping causes specific nutrient deficiencies)

More than 10,000 chemicals are approved to be added to the food we eat every day for the purpose of maintaining the quality of taste, freshness, texture, and appearance. (65)

More and more evidence is surfacing showing that many of these chemicals are significantly harmful to people’s health.

The good news is FDA regulations require that food additives are listed on the label of food products with minimal exceptions. This being said, these additives are often grouped together in labels such as “artificial flavors” or “ artificial colors”.

Children are at most risk of the toxicity effects caused by the ingestion of food additives due to their susceptibility to lower doses and still developing bodies. Harvard and Forbes warn about a few additives in particular which are listed below:

Check out foodstandards.gov for a more comprehensive list of additives.

Phthalates are known endocrine disruptors that have been linked to causing obesity, cardiovascular disease, and more. ( See the Phthalates section above for more information)(68)

Similar to phthalates bisphenols are known endocrine disruptors that interfere with puberty and fertility. Additionally, they have been linked to obesity, immune dysfunction, and neurological disorders. Lines on the inside of soda cans, register receipts, plastic wrap, plastic bottles, and babies’ sippy cups are just a few places BPAs are found. ( See the Bisphenol section above for more information) (68)

PFCs are commonly found in grease-proof paper, cardboard packaging, and more. They are known to immune system and thyroid dysfunction, difficult fertility, and low birth weights. (68)

Perchlorate can be found in certain drinking waters and dry food packaging, yet it is known to cause thyroid dysfunction and disruption to early brain development. (68)

Artificial food colors are commonly found in all sorts of packaged foods, but primarily those foods marketed to children, the exact population most sensitive to them. These food colors are known to cause hyperactivity and ADHD. (68)

PHVOs, most commonly known as trans fats are commonly used in margarine, vegetable oil shortening, packaged foods, and fried foods to increase shelf life and flavor stability. It is well known that these PHVOs are linked to causing cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, short pregnancy terms, increased risk of preeclampsia, colon cancer, diabetes, obesity, allergies, and neurological and vision disorders in infants. Be aware that food products are able to label themselves as “trans-fat-free” and still contain up to a gram of trans fat. So be sure to look for the terms “hydrogenated” or “partially hydrogenated” oils in the ingredients section of all food products! (70,71)

BHA is used as a preservative in many packaged foods such as potato chips, butter, dried foods, and beverages such as instant mashed potatoes, meat, beer, and more. BHAs are considered to be human carcinogens, with consumption showing an increased risk of liver cancers specifically. (77)

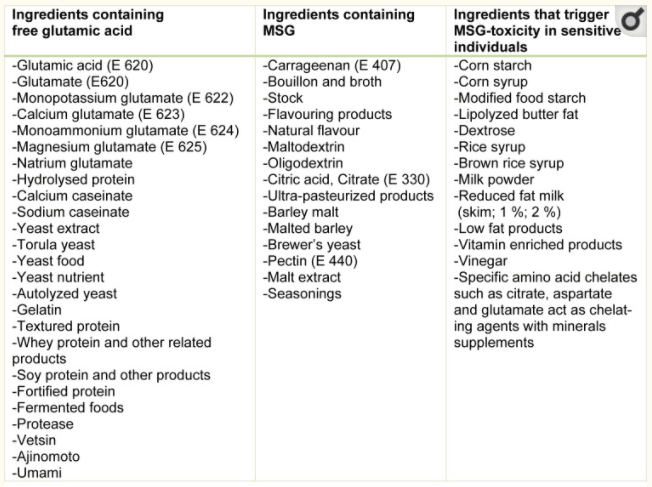

Although MSG is naturally found in certain foods such as tomatoes it is often used as a food additive to enhance flavor. MSG is commonly found in Chinese food, canned vegetables, soups, and processed meats. Although it is “generally recognized as safe” it has been shown to cause many adverse effects and even increase the risk of more serious disease. For example, it is well known that MSG as a food additive is likely to cause the following unwanted symptoms commonly known as “ Chinese restaurant syndrome”: headaches, flushing, sweating, facial pressure or tightness, numbness, tingling or burning in the face, neck and other areas, rapid, heart palpitations, chest pain, nausea, weakness. In addition, it has been shown to cause obesity, neurotoxicity, asthma, and detrimental effects on the reproductive system. See the table below for examples of MSG labeling on food products. (72,73)

(9)

Olean, aka Olestra, is a fat alternative that adds no calories to food products, often used in high fat low calorie or diet food items, such as potato chips and other snack foods. Olean is shown to inhibit the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins such as Vitamin A, E, D, and K with the potential to lead to nutrient deficiencies. In addition, the consumption of Olean has been linked to GI distress and stool changes. (74)

Many different types of artificial sweeteners have been developed over the years to decrease calorie count in food and attempt to decrease the risk of obesity. It is now well documented that these artificial sweeteners come with their own risks such as brain tumors, bladder cancer, allergies, seizures, and ironically weight gain. A few of these sweeteners also referred to as sugar alcohols include aspartame, saccharin, sucralose, neotame, neohesperidin. (75)

Carrageenan is a thickener, emulsifier, and preservative often found in dairy products such as milk, cheese, and ice cream. Despite having been shown to be a human carcinogen with links to colorectal cancer, carrageenan is still widely used in food products. In addition, it has been linked to the development of irritable bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis. Ice cream is many people’s guilty pleasure so be sure to check the label prior to picking up your next carten. (76)

Nitrates and nitrites are commonly found in processed foods especially meats, utilities for their preservative effects and color enhancement. Despite having been shown to cause thyroid dysfunction, inhibition of the blood’s ability to deliver oxygen to tissues, and even cancer, nitrates and nitrites are still approved food additives today. (68)

Xenoestrogens are a broad range of compounds that imitate estrogens once they enter the body. These compounds are found in both natural and synthetic sources having beneficial and extremely harmful effects to health respectively.

Natural xenoestrogens primarily include phytoestrogens or plant-derived xenoestrogens also known as dietary estrogens. Common sources for phytoestrogens include soy, flaxseed, bean, sprouts, cabbage, hops, garlic, onion, tempeh, sesame, wheat, fungus, coffee, plums, pears, apples, grapes, and berries. (78,79)

These natural phytoestrogens have been shown to have a wide range of beneficial effects on health including:

Synthetic xenoestrogens on the other hand are known to cause havoc in the body resulting in many unwanted health side effects. By mimicking the effects of estrogens, xenoestrogens bind estrogen receptors throughout the body causing a temporary or permanent alteration in signaling to the brain, pituitary gland, gonads, and thyroid.

Some of the most common sources of synthetic xenoestrogens include:

Phew! That was quite an extensive list that we covered, but to tell the truth thats just some of the most commonly encountered toxins in daily life. There are actually so many more that we didn’t touch on.

To recap we covered toxins found in everything from our food, and cleaning products, to plastic bottles, and even baby toys!

If you were shocked and even disgusted at some of the locations these toxins are hiding you are not alone. To top it off U.S. regulations for use of known toxins tend to lag behind much of the world.

We may not be able to change these regulations quickly but we can avoid purchasing products that include these toxins. The golden rule of environmental medicine after all is “Avoidance, Avoidance, Avoidance”.

My hope is that this article will help you to clean up your environment, limit your toxin exposure, and live your best life.

References